19.07.2018

Hutsuls and a collective farm: how the soviet system cultivated beets in the Carpathians

19.07.2018

Hutsuls and a collective farm: how the soviet system cultivated beets in the CarpathiansThe soviet experimental introduction of collective farming in Hutsulshchyna failed rather quickly. In spite of all efforts of communist agronomists to subdue rocks, beets and cereals refused to grow in the highland. Also Hutsuls could not adopt the collective method of farming.

Rich owners engaged in logging, folk crafts, mountain valley farming have always lived in Mykulychyn, one of the largest villages in the Ukrainian Carpathians, which history extends back over seven centuries. A horse laden with the wooden casks with brynza (sheep’s milk cheese) was depicted on the ancient arms of the village, the governmental seals of Austro-Hungarian period. 1934 according to official statistics there were 220 horses, 991 heads of cattle, 1209 sheep in the village.

During the years the polish orders passed over in Mykulychyn, the war went by as the bloody tornado, and in the late 40s of the 20th century the forced collectivization began. Some people found a job in the logging depots or educational, medical, cooperative institutions in their native village; many people every day went to work to Yaremche and Vorokhta.

Soviet past of Hutsulshchyna

Year 1947 went into the history of Mykulychyn as a year of preparation and organization in the village of a new farming form – a collective farm. Of course, there was not enough an arable land in the mountain village, so it was decided to create a collective farm with the livestock bias. The best of rich owners such as Hundyak, Onuchak who owned the whole mountain valleys were repressed.

Year 1947 went into the history of Mykulychyn as a year of preparation and organization in the village of a new farming form – a collective farm. Of course, there was not enough an arable land in the mountain village, so it was decided to create a collective farm with the livestock bias. The best of rich owners such as Hundyak, Onuchak who owned the whole mountain valleys were repressed.

The community of Mykulychyn, like hundreds other villages of the Carpathian region painfully came through the “voluntary” collectivization. Already since 1947 the district committee of the communist party in Yaremche actively took measures to attract the locals into the farm. The owners were called to the village council and frightened, threatened, forced to write or to sign the statement already prepared in order to join the farm. The authorities took on the collectivization of livestock, grasslands, forests, miniscule strips of the arable land.

The collective farm in Mykulychyn was decided to be called in the name of Mykyta Khrushchov, and already in the late 50s before its breaking up it was renamed to Lenin. There is no certain information about Khrushchov’s visit to Mykulychyn, but about his visit to the neighboring village Yablunytsa is known the following: “26/04/47 in Yablunytsa (district of Yaremche, Stanislaviv region) the members of the revolutionary fighting group OUN killed two Stalin’s henchmen and took away two komsomol cards from young communists. It is worth mentioning that this night Khrushchov has quartered in the village by protection of a great group of the interior ministry members”.

Edward Mitoraj, an intelligent and honest resident of Mykulychyn, a Pole by birth, was firstly assigned as an acting head of the collective farm. Later he worked as an accountant in this farm, and then went to Poland.

Mykhajlo Yurkevych was appointed as the first collective farm chairman, who was killed on August 5, 1950. On a clear summer day the head of the farm had dinner in the public dining room in the village center. Suddenly a boy in tears run up to him and complained that he had been beaten. Mykhajlo Yurkevych got up from the table and went out into the yard. The boy commanded by rebels fell into the grass, and the head of the farm was shot by the rebel Verediuk Vasyl with call sign “Juha”.

Mykhajlo Hutsuliak was appointed as the second farm chairman. He was told to be not local, short of stature, hunched his back. He rode into the mountain valley on your favorite gray horse. As a milkmaid told, the highlanders had never perceived this official seriously. Once, when two sheep were killed on the mountain valley, someone from the farm workers stealthily tied to the chairman’s jersey two sheep’s tails. So Mykhajlo Hutsuliak appeared on his horse and with the sheep’s tails in the village in front of the central farm building.

The third and last head of the collective farm in 1952 was Joseph Tarnavskyj, a resident of Mykulychyn who was considered to be an authoritative leader. Only because of his efforts this collective farm was hold out until 1959. The wife of the head, Nina Pidlisna-Tarnavska, worked with a hoe in the agriculture group together with all the collective farmers.

Initially, there were not many collective farmers. According to the report of 1951 there were 86 people, 34 of whom were men. Later, with the expansion of the economy, the number of the employees increased.

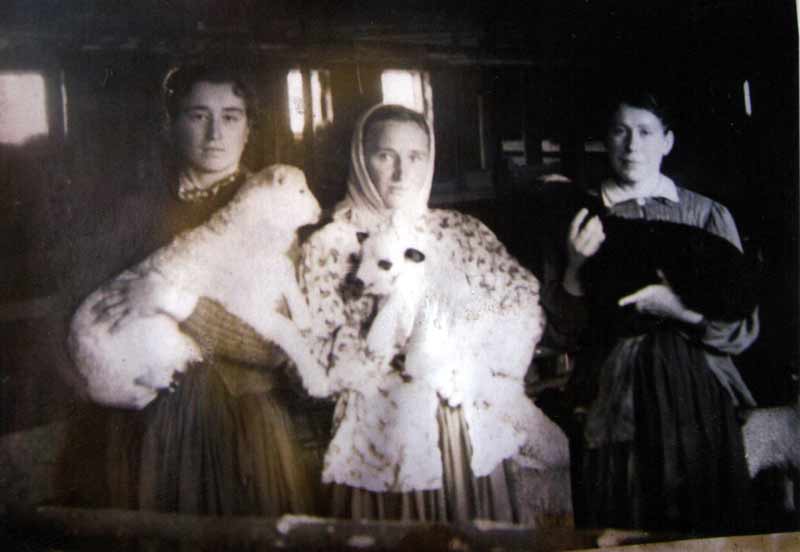

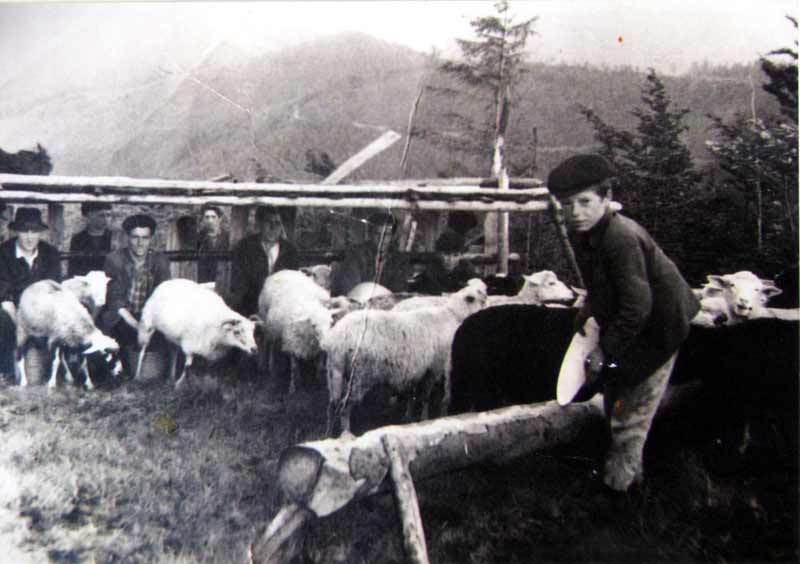

Already in 1948 the farmers began to bring sheep into the mountain valleys. Partly there were semi-fine wool sheep from the steppe regions not adapted to cold and incessant mountain rains, so they often died.

1957 the total number of the sheep in the collective farm was 709. For some reasons the sheep died. These reasons were lack of forage, inappropriate care, and natural factors. For example, in 1956, 73 sheep died. There were problems with wool harvesting. If in 1953 it was planed to clip 2.5 kg wool per sheep, the actual clip was 1.22 kg, and in some years – 0.8 kg.

1957 the collective farm named after Khrushchov had 345 heads of cattle including 142 milk cows. Of course, lack of forage caused the low yields of milk. 1953 the farm board reported that they planed to get 1450 liters of milk per one foraged cow, and 1183 liters were actually received.

Also the positive fact was that there was enough milk not only for public procurement, and so for using in own farm (in particular, feeding calves); it was allocated into an invalidity fund and for maintenance of nurseries, orphans, and a certain amount was realized in the way of the collective farm trade.

Milking a cow Carpathians Soviet times

The farm made cheese from sheep’s and cow’s milk. According to statistics, in 1952, 1,280 kilograms of the product were received.

In the collective farm, of course, the ideological work was conducted, the specifically assigned lecturers, members of communist party often appeared in Yaremche. Agitation groups came often hereto. The collective farm workers were obliged to read the local newspaper “Bolshevik of the Carpathians”. The best workers were taken to Moscow to see the exhibition VDNKh.

Delegation of Mykulychyn collective farm workers in Moscow

The collective farm named after Khrushchov in Mykulychyn was short of an arable land – there were only 65.13 ha. It was difficult to get even an average yield of crops on this marginal rock land, pieces of which were scattered throughout the village. From the earliest days of the farm’s existence the field brigade was formed. 1951 a sowing plan was given as follows: 3 hectares of rye, 7 hectares of barley, 5.5 hectares of oat and 31 hectares of potato.

Later the areas were expanded for maize and fodder beet. In one of the photographs we see Hutsul women in the embroidered blouses, which hoe the beets. Often crops were amazed by the late frosts, which were usual in the highlands. Also, the collective farm lacked agricultural machinery. The horses were the main drawing force. In 1956 there were 31 horses in the farm.

A forage base for livestock farms was totally poor; the farms constantly bought feed or exchanged it for timber. In particular, 1953 the board of the farm decided to sell 1000 cubic meters of wood at the price of 48 rubles per standing one (buyers themselves obliged to cut down and remove the logs) to the farm workers of Kryzhopil district of Vinnytsia region. This is not a separate case. An income and expenditure estimate of the farm was carried out due to timber. The collective farm had its power-saw bench, income from which, in 1955, was 70 000 rubles.

It should be noted that the total area of the farm land was 4809 hectares, including land area covered by forest – 1933 hectares, i.e. 40% of the farm area. Except the main area, the forests in the mountain valleys were accounted: Yavirnyk – 9 hectares, Barnya – 48 hectares, Khomyak – 77 hectares, Polyanytsya Chemyhivska – 23 hectares, Shkrumivka – 29 hectares, Lisnovy – 97 hectares, Hrun – 20 hectares, Shekelivka – 194 hectares.

The socialization of valleys, meadows, harvesting and sale of timber displeased the residents of Mykulychyn. The livestock in the private farms decreased as a result of revising land area by the collective farm. The forest guards also sounded the alarm.

At the end of 1958 a commission of the Ministry of Agriculture of Ukrainian SSR came to Mykulychyn to investigate the activities of the collective farm. The officials’ conclusions were onevalued – the farm had to be liquidated. It turned out that the mountain climate was unsuitable for the communist economic system.

February 20, 1959 the collective farm named after Lenin in Mykulychyn was already reorganized into the subsidiary farm of forestry. The forests and lands, inventories, buildings and documentation were taken from the collective farm. That was the end of the ten-year collective farm epopee in the mountain village, about which only a few people of the current residents of Mykulychyn know.

-

27.02.2024

World of pysanka

Embark on a journey into the captivating world of Pysanka, the Ukrainian...

27.02.2024

World of pysanka

Embark on a journey into the captivating world of Pysanka, the Ukrainian...

-

29.01.2024

Exploring the Treasures of Kyiv’s Lavra Monastery

In the heart of Kyiv lies the venerable Lavra Monastery, a testament...

29.01.2024

Exploring the Treasures of Kyiv’s Lavra Monastery

In the heart of Kyiv lies the venerable Lavra Monastery, a testament...

-

13.01.2024

Kachanivka, Eden on Earth

Rich in history, it hosted renowned artists, notably poet Taras Shevchenko.

13.01.2024

Kachanivka, Eden on Earth

Rich in history, it hosted renowned artists, notably poet Taras Shevchenko.